Column

Less for More

Necessity is the mother of invention, as we all know. And the fact that the same applies to residential buildings is evidenced by a block of flats designed by Ben van Berkel that is currently under construction in Munich. The developer is Bauwerk Capital, a Munich-based company that calls itself a visionary project developer and is, logically, marketing the project as “the answer to the housing questions of our times.” Despite everybody constantly banging on about Covid, this does, for a change, remind us once again about the housing crisis, caused, among other things, by soaring land prices. Nowadays even investors are struggling to keep up with this because the building advertised as “Van B”, the name of which bears the initials of its author, has to contend not only with its location in the no-man’s land between the districts of Schwabing-West, Neuhausen-Nymphenburg and Maxvorstadt, but also seemingly needs to provide an answer to the question of how to squeeze as many apartments as possible into one single item of real estate.

Interestingly, despite its name, the results are not, by any means, reminiscent of van Berkel and his UNStudio but are more likely to call to mind a horizontal version of the Nakagin Capsule Tower by Kisho Kurokawa, crossed with David Chipperfield’s concrete classicism – that’s Munich for you. And on the inside? Here, the talk is all about “flexible spatial structures which adapt to life in ever new ways.” And then “with something like this, it is no longer the size of an apartment that matters, but how intelligently it is used – a revolution.” Yet when looking at this revolution and the renderings of it, it is inevitably student dormitories or business hotels with their windowless bathrooms that spring to mind, only this is one with more bling-bling on the surface. With 90 of the total of 142 apartments we are, in fact, talking about single-room units offering a living space of between 33 and 44 m².

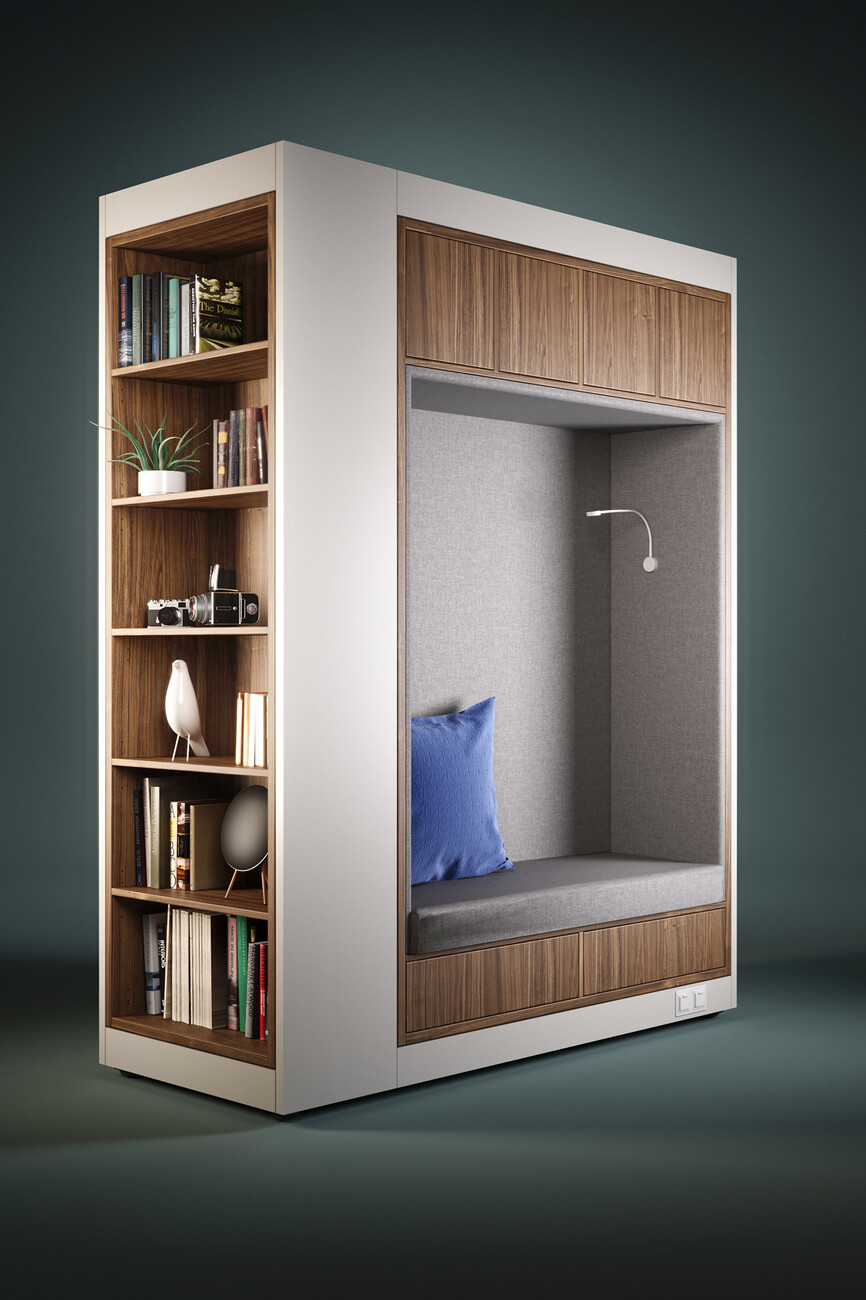

This being the case, the architects have thought up something to evoke a remote sense of spaciousness. Fitted out with cabinet furniture, so-called “plug-ins”, that run on tracks and are destined to fulfill various functions such as that of a bed, kitchen or storage room, the units can be zoned flexibly – an apartment metabolism light as it were. However, if lack of space means having to come to terms with a sofa-bed, we can assure you that over time all that folding out and putting back together again can start to get on your nerves. As for the larger apartments, it is the three-story “gallery lofts” on the ground floor, with two of those stories at basement level, that represent the most interesting option. At least these have their own yards.

Of course, the euphemistically pimped up superlatives in the marketing brochure that describes the product of a difficult overall situation as “very urban living” are just setting themselves up for a hatchet job. Nevertheless, to the project’s credit it should be mentioned that at least it does attempt to be innovative. Indeed, to a certain extent “Van B” is reminiscent of the kind of cooperative or participative projects that also ask themselves about how people want to and can live together. The magic word here is “community” because the Van Berkel project also sees itself as a “community building” that offers communally usable rooms for its residents and the possibility of co-working. It also provides sharing vehicles in its underground parking garage.

The fact that the middle class’ dreams of owning their own homes have come to nothing is demonstrated by another investment project in Berlin. There, a Munich-based project developer by the name of Euroboden is currently planning two residential buildings in a similarly difficult location using a type of development that, like no other, exemplifies welfare housing schemes – the “covered outside walkway”. In the case of Euroboden, this has manifested itself in a Neo-Brutalist building in which the covered outside walkways also serve as communal zones – that’s Berlin for you. And so, architects are currently re-cycling old familiar 20th century concepts which, to paraphrase Frank Zappa, were perhaps not dead, but just smelled funny. Things appear to be changing at the moment and of course the question arises as to whether this is good or bad. The answer is to be found in every individual’s design for living and in the salary that they have at their disposition and it is, to slightly modify another familiar quotation: “Less for more”.